Yes, another column that starts with this disturbing piece of statistic. But I must: India’s court system is crumbling under a colossal backlog with over 5 crore cases pending as of 2025.

But what’s important and often missed, is that nearly 90% of all of these cases sit in the trial courts — the first and, often, the only layer of the judicial pyramid that most citizens ever personally encounter.

In other words, the very foundation of our Justice System.

Trial courts are where justice is most visible and most immediate, yet their judges face an uphill battle daily.

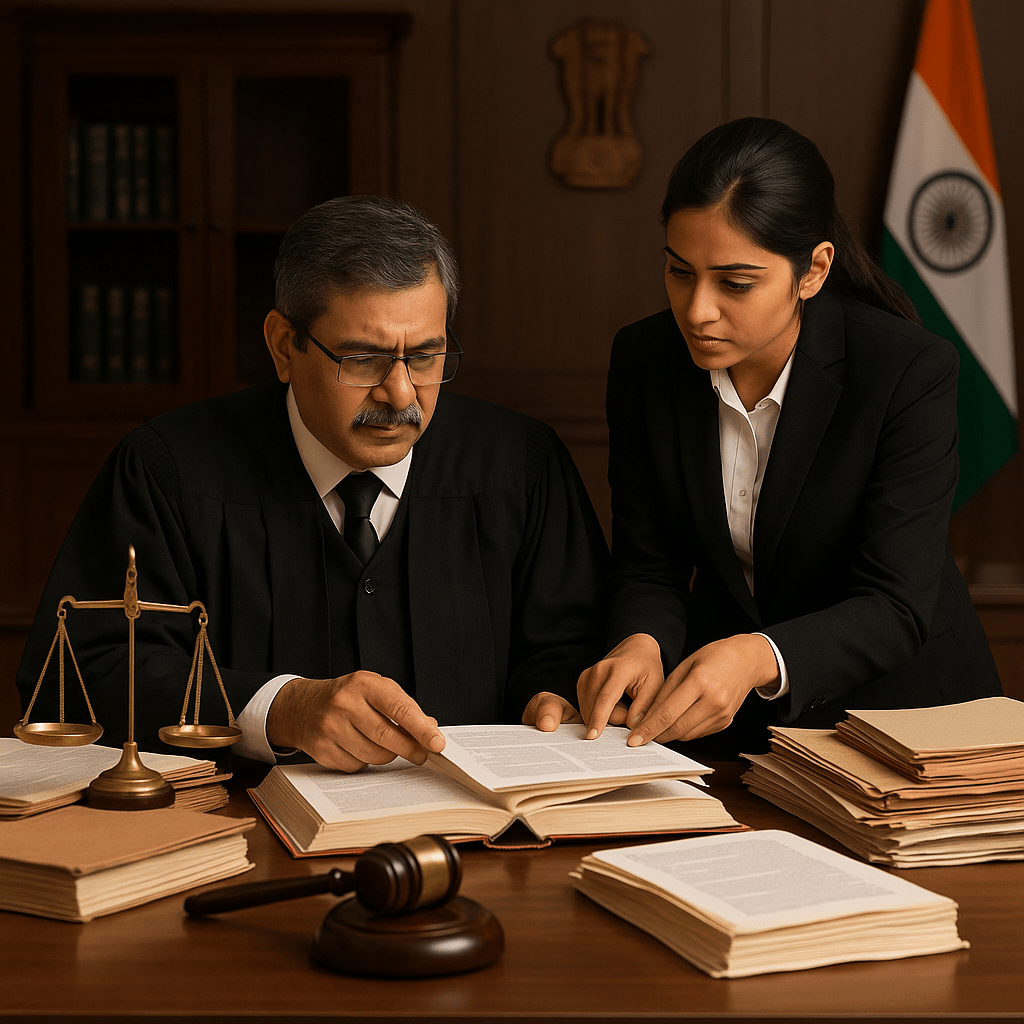

They manage massive cause lists, conduct time-consuming procedures (like TIPs inside prisons), record dying declarations, take confessions and statements under Section 164 CrPC, decide bail & remand applications, record evidence of dozens of witnesses, perform administrative tasks such as manage, monitor and grade their staff, cover “link duties” for absent colleagues, and while doing all of that also conduct full-fledged trials. Trials with grave factual and legally complex issues. And, all of this, essentially with no legal research support.

Speaking from experience, when I first took charge as a young magistrate of 23 years, my court had over 5,000 pending cases and 125–150 matters listed each day. This, apart from, all that I’ve mentioned above & link duties of about 6 other courts (to handle their work when they go on leave or are busy with administrative duties).

Now, even with the best of intentions and giving one’s all, I almost always went back home with a heavy conscience and with the thought that – may be – if I tried harder I could’ve granted a shorter date of hearing in that one case, or prioritised that one case a bit more where injustice was so manifest and may be stretched my day a little bit more.

This feeling is – by no means – uncommon in the life of a trial judge. But, again, you have only so much you can do, when there’s such little assistance.

But, coming back, trial courts are the very foundation of justice for ordinary citizens. But this foundation, even with some very bright minds, is currently weak due to pendency, work-load and – most importantly – lack of legal assistance and these cracks in the foundation are threatening the very edifice which cannot – now – stand firm.

In contrast to this relative lack of assistance/resources, higher/constitutional Courts often have weeks (and sometimes, months) to write decisions even with the assistance of best legal counsel, amici curiae, and the support of hand-picked clerks/LRs and a retinue of law interns.

Trial judges, usually younger and relatively less experienced, must think on their feet and deliver orders & judgments much sooner, and often without any assistance.

Though the situation may be somewhat better in areas such as Delhi, I’ve heard far too many young judges (at judicial academies), serving in remote districts, telling me that – often – all that a lawyer argues in front of them is “Janaab, jo behtar samjhein, kar dein!” (Mylords may decide whatever Mylords deem best/fit), without the slightest assistance on factual or legal side. This, over and above, the constant basic infra issues such as lack of a stenographer and computers not working….

These difficulties are often exacerbated in our legal system where – unfortunately – appellate benches (of equal strength) often end up issuing conflicting rulings, leaving trial judges struggling to understand the correct precedent to apply in a given case at hand.

An illustration at hand is the recent debate on whether “grounds of arrest” must be given in writing or can those be given orally also, at the time of arrest, and ‘whether violations of this rule automatically entitle arrestee to bail or should courts follow a prejudice test’ is a classic example of co-ordinate benches of higher courts sometimes laying down seemingly disparate law and without larger benches settling the law for guidance of the trial courts across the country who have to grapple with these issues daily.

Trial judges confront these dilemmas daily, without research support, and under immense pressure, and in situations, where time is of the absolute essence.

And this is a vicious circle as small mistakes at this stage then ricochet upwards, consuming time in High Courts and the Supreme Court — which spend hours and hours deciding regular matters such as bail or interim injunctions.

Strengthening trial courts would reduce this trickle-up burden and free up judicial time of higher courts to decide the truly novel and truly difficult interpretational, legal and constitutional questions.

And which, by the way, is a virtuous circle, as more clarity on interpretational questions & a careful restatement of principles of law for trial courts would introduce certainty of legal doctrine and minimise errors, which – again – frees up appellate dockets to focus on issues of general public importance.

The Support Gap

The contrast is stark.

- As I’ve argued earlier, the Supreme Court and High Courts often, apart from having best legal counsel (representing each side), amici curiae, also have multiple law clerks/LRs, usually hand-picked amongst one of the brightest young law graduates, selected by a painstaking process, assisting with research and drafting, and compensated suitably and commensurately. This is over and above the multiple law interns (law students) that are also available for assistance.

- Trial court judges have none. Not even one.

This structural gap leaves trial courts perpetually disadvantaged. Even basic interpretative questions — say, about the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) or Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS)— must be answered on the spot, without the support of research.

Unsurprisingly, hurried judgments (often on legally virgin or shaky territory!) are sometimes vague or legally shaky, and appellate courts regularly highlight factual or legal errors, and sometimes also go on to the extent of passing strictures against trial judges.

Thorough research at trial would reduce such errors, saving appellate time and improving litigant trust.

Why Law Clerks/LRs Matter

Appointing clerks for trial judges would make a lot of difference:

- Better-Quality Judgments

Clerks can review statutes/rules/bye-laws/notifications, track new amendments, read and reconcile/harmonise new judgments, prepare bench briefs, help with factual aspects such as list of dates, exhibits, etc. Judges then have more time for analysis/appreciation of evidence instead of scrambling for authorities. They can also fact-check precedent relied upon by counsel, which – unfortunately sometimes, does not present the whole or correct legal picture, and may have been overruled, nuanced or distinguishable, and the trial judge often does not receive that important information. - Fewer Weak Appeals and focus of higher courts on issues of law

Sound trial decisions are harder to challenge. Appeals decline in number or become easier to dismiss, freeing High Courts to focus on complex constitutional and interpretive questions. - Empowered and mentally stimulated Judges

With research offloaded, judges can concentrate on recording of evidence (the very core of trial judging which is sometimes neglected or delegated), courtroom management, and verdict-writing. This also makes their work more efficient and intellectually rewarding, improving morale and help them be more updated on the law, which – in turn – makes them more confident in the conduct of their court, less prone to being misled, and overall, sharper/better motivated and more involved in the justice delivery process. - Ahead of the curve: Also, the landscape of litigation work is fast-changing and our adaptation of latest tech is something we need to work on. Introduction of young LRs/Law Clerks may assist our more senior members of trial judiciary to transition to new technologies faster and smoothly and learn new laws (such as those relating to data protection, AI, deep-fakes, cyber crimes, cryptocurrency, IPR, etc) more quickly and stay abreast of the latest in the law. Both generations gain from each other’s vast experience.

- Training the Next Generation

This is important but not often talked about. Clerkships also expose bright young law graduates to trial court practice — courtroom procedure, evidence, and grassroots realities. Many go on to be better litigators, prosecutors, or even judges. This may encourage young law graduates to take up trial court work (either as prosecutors or defence counsel) or even trial court judgeship (which is currently facing a huge talent crisis). This also revives much needed respect for trial practice and judgeship, which is often dismissed in favour of corporate or appellate work. (This would be an unseen positive consequence of this practice). - For young graduates, these roles can be truly transformative. Instead of heading straight to law firms, many may embrace the intellectual stimulation of trial court work — serving in rural or under-served courts, and seeing firsthand how law changes lives, which is – both – deeply rewarding on a personal level, and also goes on to serve the cause of access to qualitative justice, till the very last person.

Also, the potential cost argument is somewhat misleading. Hiring clerks is – in fact – extremely cost-effective. One clerk costs a fraction of a new judge or a new courthouse, yet empowers and multiplies a judge’s effectiveness exponentially. Instead of simply fixating on the problem of less number of judges, we ought to – now – think about empowering the ones we already have by supporting them well.

Conclusion

Trial courts are India’s frontline of justice. They decide the fate of millions and carry nearly 90% of the judicial backlog.Yet their judges work alone and without the legal support.

If India is serious about reducing pendency and restoring public faith in the rule of law, it must start where the problem is heaviest: the trial courts. Law Clerks/LRs for trial judges are not a luxury. They are a necessity.

Even one good law clerk/researcher per judge can help millions secure timely, well-reasoned justice.

And, the very foundation of our justice system deserves nothing less.

Disclosure : The Author was a member of the Delhi Judicial Services from 2013-2016 before returning to the practice of law.

Leave a Reply