*Caveat : This piece was written on the first draft, that is, before the first draft went to the Select Committee and a new version was put up for consideration and finally passed by the Legislature.

A lot of you have written to me, over the past few weeks, seeking my views on the New (proposed) Indian Criminal Laws.

Here’s then – in no particular order – a few thoughts on the New Indian Criminal Laws, bucketed, for convenience, under the three separate heads and covered in three separate blogs :

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Please, and at the very outset, allow me to caveat this with : This is only a preliminary view on some of the changes and this piece is neither exhaustive nor final. In any event, no estoppel against counsel!

Well, without further ado, here’s part 1.

1. The Good

1.1. Introduction of certain non-stigmatising concepts seems like a good step; for instance, the recognition of ‘mental illness’ as a concept (as opposed to the relatively archaic concept of ‘unsoundness of mind’ and connecting it to the Mental Health Act is a step – I feel – in the right direction.

Having said that, any positive effects may remain only symbolic (for now) because of a failure to properly engage with the now-obsolete legal insanity test/threshold, which still prevails and has been retained in its original shape.

More nuanced concepts of diminished responsibility and impact of other mental illnesses (falling short of the very high standard of legal insanity), it appears, have also not been examined.

Further, as my colleague Hamna Rehan points out, the concept of “mental illness”, as defined in S.2(s) in the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 also excludes from its ambit “mental retardation”. This may need some deliberation.

The new additions under this head, for convenience, are as follows:

S.2(19) BNS[1], 2023

S.22, BNS vis-à-vis S.84 IPC

The earlier law stood thus:

1.2. Definition of Moveable Property (S.21 of BNS and 22 of IPC) has been amended and – arguably – widened to include even non-tangible/corporeal moveable property.

But this (ostensibly) progressive amendment, it appears, has not been followed-through with a corresponding amendment, for instance, in the definition of the offence of theft, where, for instance, the aspect of ‘moving’ of property still remains the Actus Reus (Alien for : the act/consequence needed and made culpable by law).

This may be problematic. For instance, in a case of unauthorized data theft by copying , there is no aspect of ‘moving’ of property; therefore, the new definition of moveable property may still not capture cases of data theft, without a corresponding amendment in the definition of theft.

This is, of course, without prejudice to the fact that this instance may be covered in S.43 r/w 66 of the IT Act.

The relevant provisions being compared are as follows:

S.21, BNS vis-à-vis S.22, IPC

The earlier S.22, IPC

S.301, BNS is same as S.378, IPC

1.3. Death by Rash and Negligent Acts may now warrant punishment of upto 7 years and, in cases of hit-and-run, even 10 years.

This is – broadly – a good one.

The offence also appears to be non-bailable offence, now.

Punishment under the earlier S.304-A of the IPC was not at all proportional to the gravity of the offence and a lot of cases fell between the large and gaping void between 304-A IPC (too lenient) and Culpable Homicide (too serious, and with a very high mental threshold).

This may introduce some real deterrence to rash and negligent driving and ensures such accused are not let-off with a mere rap on the knuckles.

The heightened punishment for hit-and-run cases is also a good step.

Be that as it may, the application of this section to other cases of negligence may, in some cases, mete out great hardship given the relatively low standard of mens rea needed : Rash and Negligent Act. What would have been helpful is – some guidance on distinction between mere negligence and the gravity/level of negligence needed to make out criminal liability i.e gross and culpable negligence/recklessness.

Relevant changes in this regard are as follows:

S.104, BNS

On 104(2) BNS, what may be worthy of examination is whether the ‘duty to report the incident’ runs foul of the guarantee against self-incrimination and the accused’s right to silence.

At least on the first blush -it seems that it may not be. Reporting the incident is not the same thing as being compelled to be a witness against yourself.

Especially in cases where the accused was not negligent but the victim was. In those cases, reporting the incident is not tantamount to ‘being compelled to be a witness against oneself’. In other words, Every reportage is not a confession.

Also, there appears to be a two fold duty on such an accused now : First, not to escape, and report the offence. Leaving the scene of crime with a view to report (for instance, if one doesn’t have a phone) should not normally violate this section, given the intent of the law.

Further, on what qualifies as ‘escape’ and what really would be considered ‘soon after the incident’, is essentially a fact-intensive exercise. I believe the clear intent of the law i.e : to ensure that victims get proper medical treatment in time would help the courts and lawyers interpret the law in its right spirit.

Earlier S.304A, IPC, for reference, read:

Now onto some procedural changes:

1.4. 154(3) CrPC made mandatory. We all know that if police doesn’t register FIR in a given case, one may approach the area magistrate.

By virtue of various judicial decisions, a direct recourse to the magistrate (without approaching the police and without escalating matter to senior authorities) was not possible.

This proposed amendment recognises and makes this prevailing legal position explicit.

Approaching the police authorities (and escalation of matter to senior officers) first and before filing a 156(3)application before the Court is now mandatory.

This is an important safety valve.

Further, the magistrate while deciding whether to order registration of FIR or not, must consider the report filed by the police in that regard.

This is a recognition of the concept of ATR/Status Reports, which is essentially a creation of judgments on the subject.

The current provision.

S.154(3), CrPC:

S.36 CrPC is also relevant in this regard:

The new provision:

S.173(1), BNSS[2]

S.173(4), BNSS:

Section 175(3), BNSS:

1.5. Statutory recognition of the concept of ‘Preliminary Enquiry’ –

Broadly, an important statutory recognition of the concept of ‘Preliminary Enquiry’.

This concept, I must add, is not a new one. Even the Punjab Police Rules, for instance, recognised the concept and provided for PE before the registration of FIR.

But this amendment makes it clear.

Now, in certain cases, the police can conduct a preliminary enquiry (“PE”) to ascertain whether there exists a prima facie case for proceeding in the matter.

This PE has also been made time-bound and required to be completed within 14 days.

This – on a first reading – seems good. There are many cases where an immediate registration of the FIR may pose considerable hardship and mischief to innocent accused.

Having said that, the broad class of cases in which PE should be conducted must be expressly spelt-out to : i) control the police officers’ discretion; and ii) check and prevent abuse in a class of cases where there are high chances of abuse.

And this is not a new idea. In the case of Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of UP [2013 SC], the SC laid down guidelines and provided for PE in a certain class of cases. Here – PE was held to be appropriate in matrimonial cases, commercial disputes, cases of medical negligence and complaints with huge delay; in all of which there are very high chances of the process of criminal law being misused.

So, all in all, recognition of PE is a good move but the reform doesn’t go far enough.

The proposed relevant provision in this regard i.e S.173(3), BNSS now reads:

1.6. MANDATORY FORENSIC TEAM/VISIT :

The new addition makes visit and investigation by the Forensics team/Crime at the scene of crime mandatory in cases punishable with greater than 7 years imprisonment.

This is a good step and would prevent important evidence from being obliterated in many a cases.

It reads:

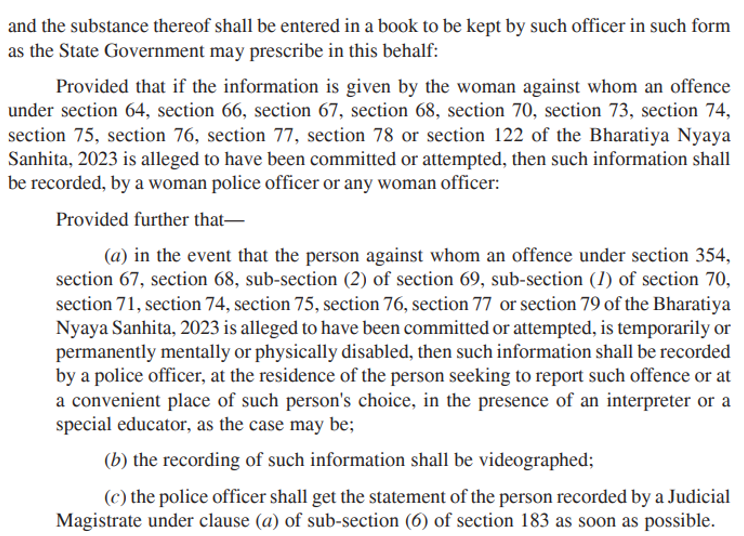

1.7. Recognition of electronic/audio-visual recording of : FIRs, statements, made during investigation and at trial.

1.7.1. Recording of FIR on the basis of electronic communication:

S.173, BNSS vis-à-vis S.154, CrPC

1.7.2. : Recording of statements made in the course of the investigation electronically:

S.180 (3), proviso, BNSS

S.254, BNSS: Recording/deposition of evidence by electronic means

S.532, BNSS, a new general provision has added for conducting Trial and Proceedings in electronic mode:

1.8. Victim’s right to be informed :

Also, noteworthy is the right of the Victim to be informed of the progress of the Investigation within 90 days of the commencement of the investigation.

This, too, is indeed a welcome step.

Victims have traditionally been consigned and confined to the footnotes of criminal investigations and trial. This is an important recognition of their rights.

This would also enable them to prepare for filing of protest petitions (in a timely manner) – in case the police takes a decision not to investigate the matter further.

The relevant provision in this regard reads as follows:

S.193(3), BNSS vis-à-vis S. 173, CrPC

1.9. Supply of the police report/documents to the Victim (and not just to the Accused).

The relevant provision in this regard reads as follows:

S.230, BNSS

Earlier S.207, CrPC read as follows:

1.10. Dropping of proceedings/ discharge in a Summons case.

This is important and a good step which wasn’t possible under the earlier avatar of S.251 CrPC which, in a summons case, only talked about ‘explanation of the substance of the accusation to the accused’ and did not envisage a discharge or dropping of proceedings at that stage.

To recall, in Warrants and Sessions cases, the court was specifically empowered to discharge the accused if no prima facie case was made out.

But this power was absent in summons cases. This was by design and not accidental. The original intent behind this omission was to carry out summons cases/trials fairly quickly and in a relatively more abridged format.

But given how long even summons cases last in the country, this is a welcome addition. There is no reason as to why an accused in a summons case should be worse-off than an accused in a warrants case and not be entitled to this very important remedy, especially in patently meritless cases (which should be thrown out at the very outset)

The new provision reads as follows:

S.274, BNSS vis-à-vis S.251 CrPC

Earlier S.251, CrPC read as follows:

1.11. Clarity on further investigation post commencement of trial.

The law on further investigations (“FI”) and permissibility of FI post framing of charges/ commencement of trial was (and is) far from clear.

The new proposed S.193(9) BNSS provides that FI after framing of charges, would be permitted only with court’s explicit permission and the same has to be completed in 90 days or any other extended period that the court may grant.

This is a welcome move.

There is a disturbing practice prevalent currently where the police keeps filing supplementary chargesheets and introducing new facts and evidence.

This amounts to – sometimes – changing the goal-pasts long after the game has begun.

This provision may check this pernicious tendency of filing multiple charge-sheets – with a view to spite the Accused.

This may also ensure – to some extent – (and indirectly) that the police files a chargesheet only after a proper completion of the investigation and not an incomplete chargesheet merely with a view to defeat the right of the accused to default bail.

S. 193(9) Proviso, BNSS

Earlier avatar i.e S. 173(8), CrPC read as follows:

1.12. Now, a Discharge Application has to be filed within 60 days of committal of the matter:

This is a good move and may help expedite matters.

With the caveat, of course, that, experience has shown that time-lines such as these are honoured more in breach than in compliance. (especially, if no specific consequence is provided in the law itself).

S.250, BNSS vis-à-vis S.227,CrPC

1.13. Direction to every State Government to prepare and notify a Witness Protection Scheme

Frankly, though we’ve classed it here, I don’t know if this does any real good.

State governments may choose not to have and/or not to implement the respective state schemes.

A real good step would have been to lay-down a chapter within the Criminal Procedure Code spelling out mechanics of witness protection and fixing responsibility.

This would have ensured greater sensitisation and compliance.

S.398, BNSS

1.14 : ZERO FIR.

This is a good move. This was already the case on account of various judicial precedents but this makes it explicit that : the police is duty bound to register FIR in cognizance offences whether or not it has jurisdiction over the case.

S.173(1), BNSS

These are my reflections on some of the proposed amendments. This is not exhaustive by any means.

There would be 2 more parts on the not-so-desirable parts of the new Criminal Laws which would follow shortly.

Many thanks to my brilliant co-counsels and interns at the Chambers for the thought-provoking discussions and all the help.

Thank you Shubanshi and Arusa for helping me put this together.

Part 2 is now out. You may read it here

[1] Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (hereinafter BNS)

[*BNS Bill seeks to replace IPC, 1860]

[2] [2] Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita Bill (hereinafter BNSS)

[*BNSS Bill seeks to replace CrPC, 1973]

Leave a Reply