The settled law with respect to Section 200 CrPC was :

In a complaint case (private prosecution) an accused person does not come into the picture till process(summons or warrants) is issued. And process, we all understand, is issued after the judge examines the complainant, records what is known as pre-summoning evidence (PSE) & finds a prima facie case in favour of the Complainant and sufficient grounds for believing that an offence has taken place and accused has committed that offence.

This is essentially a matter between the court and the Complainant. The accused has no locus standi to appear and argue before he or she is summoned in the case.

Though being summoned in a criminal case – by itself – is a serious matter, this does not prejudice the accused who gets the chance to put forth his/her case after cognizance and earn an exoneration. There are several avenues for this. The accused may, for instance, challenge the summoning order in a revision petition. The accused may also apply for quashing of the case to the High Court under Section 482 CrPC. Further, the accused may take his chances and argue for discharge before the same court, if the matter is not worthy of being taken to trial.

This was the law; well, until now.

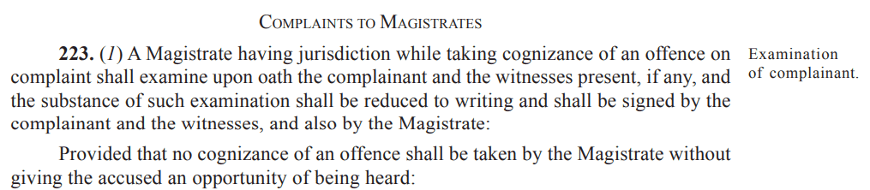

Section 223 of the BNSS (which replaces the earlier S.200 CrPC), now in force in all its glory, has added an interesting (and potentially problematic!) proviso. It reads:

Focus on the proviso.

It’s clear that – now – cognizance of an offence on a “complaint” cannot be taken by the Magistrate without giving the accused an opportunity of being heard.

Now, for those who arrived late, Cognisance, we all understand, connotes the process of : application of judicial mind by the court to the facts stated in a complaint or police report or information received – with a view to taking further steps.

It is clear that – now – the provision envisages issuance of a notice before taking of cognisance. This effectively means that for complaints under BNSS, the Judicial Magistrate must give the accused – or more appropriately the proposed accused – an opportunity of being heard prior to cognisance i.e prior to application of judicial mind.

Giving the accused an opportunity to be heard even before cognizance is taken was unheard-of in a criminal proceeding until now.

The ostensible intent appears to be to give the accused an additional opportunity to be heard & possibly to reduce chances of false implication & to allow accused persons to avoid being summoned in false criminal cases.

But the manner, mode and timing of this notice is not clear. There are serious doubts as to whether this notice to the proposed accused is to be issued after PSE or before. Is it to be issued the moment the complaint is received and registered, or after some basic inquiry into its merit?

Also, isn’t calling the accused and then hearing the accused on why he/she should not be called/summoned is a little (a lot!) counter-intuitive….

To sum up, though the intent appears to be noble, as any trial lawyer/judge would quickly observe, a few problems arise: .

- What would be the extent of the accused’s involvement at this stage? For instance, whether an accused can produce evidence at this stage or question complainant’s evidence/documents? One would think – No. The proposition laid down in Debendra Nath Padhi (SC 3 Judges) may guide in this regard. (But can the accused atleast point out suppressions/concealments and unimpeachable documents of sterling quality, as is sometimes possible before the High Court in proceeding u/s 482 of the CrPC)

- Whether the accused will be made aware of all the material against him in order to provide him a reasonable & adequate opportunity to be heard?

- Is there an application of mind envisaged before issuance of notice to the accused or is the order to be passed mechanically the moment a criminal complaint comes before the Court?

- Put differently, when a complaint is filed, will issuance of notice be mandatory, or can the Court choose not to issue a notice? If the answer is yes, in what cases can that discretion be exercised?

- What will be the administrative burden of this addition? Will this delay the initiation of criminal proceedings and taking them to their logical end?

- In case the accused chooses not to show up, will his/her right be waived off? In other words, whether the accused avails this opportunity or not is entirely his/her prerogative, or is it a duty to assist. (In all probability, the former, but we’ll wait and see).

- Will this lead to a mini-trial (or a trial before trial) at this stage which was previously only a broad satisfaction about the existence of a prima facie case?

- On one hand timelines are introduced in order to ensure speedy justice, on the other, this proviso may delay the proceedings. Would this turn out to be counterproductive?

- Can the Court refuse to take cognizance and dismiss the complaint if it concludes that the story put forth by the Accused is true?

- Will this proviso vex the prospective accused needlessly (by making them participate) even if the Court decides not to take cognizance ultimately?

Let us know in the comment section what you feel about the provision.

Also, in this regard the Savings clause would also become crucial. That’s Section 531 BNSS. Especially in the context of Complaints filed (before 1st of July, 2024) but not taken up for consideration. In those cases, one view is that since “Inquiry” commenced under the earlier law, the same would be governed by the erstwhile Section 200 CrPC and not the provision under discussion. The other view is that : procedural law operates retrospectively; and for greater reason, when we are talking about a beneficial provision, the benefit of which ought to be extended to accused in on-going cases as well. Both the views are up for arguments and we hope to deal with the same in a future column focussed on the savings clause.

Co-written by Bharat Chugh & Kritika Malik

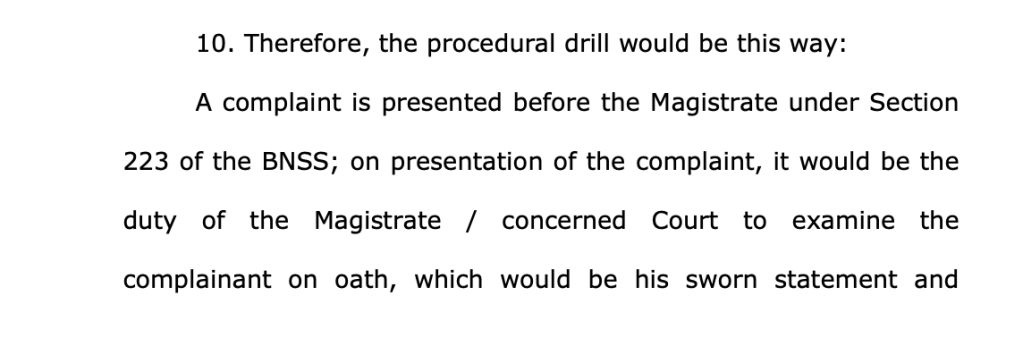

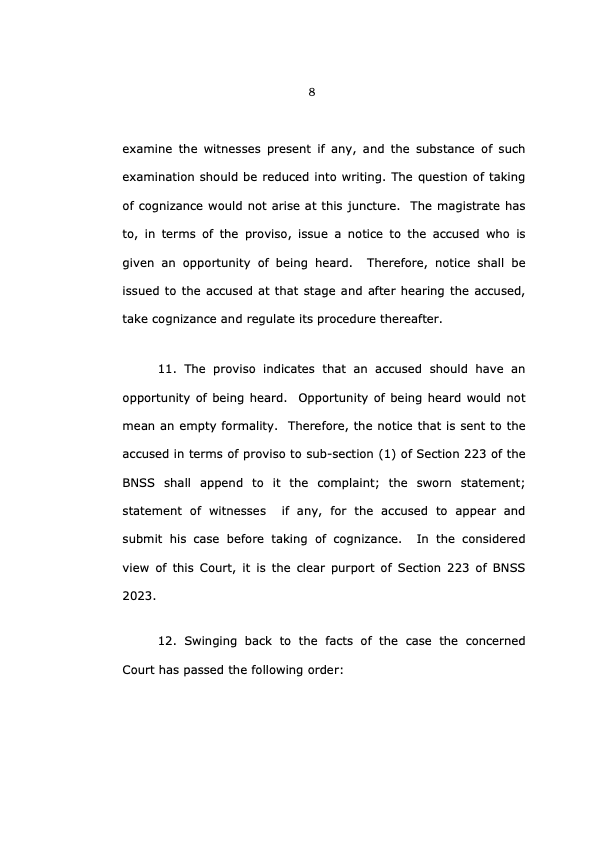

PS : After writing of this blog, my friend Lakshya brought to my notice a Karnataka HC ruling which says this on the subject:

This does introduce some clarity on a few aspects of the provision. Having said that, quite a few questions remain unanswered. We’ll address that in a subsequent post.

Leave a Reply