The BNSS (Bharatiya Nagarika Suraksha Samhita) brings about several notable reforms in the criminal justice system. One of the changes that stands out, and perhaps redeems BNSS in a significant way, is the mandatory videography of search and seizure operations. This reform addresses a long-standing flaw in the system that has facilitated abuse of power, particularly by law enforcement.

In my years in the criminal justice field (both as a Judge and as a Lawyer), I have encountered countless cases where individuals were falsely implicated. It was disturbingly easy for police officers to fabricate evidence. A narcotic, a bottle of illicit liquor, or a button-dar knife (flick-knife) would suddenly ‘appear’ during a search, and just like that, a person’s life was ruined. It’s been said—almost as urban legend—that many police stations kept troves of such items, ready to be ‘discovered’ when an inconvenient individual needed to be tripped or ‘dealt-with’.

Though the law did mandate transparency, specifically under Section 100(4) of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), which required searches to be conducted in the presence of independent witnesses, but – in practice – this provision was widely ignored. What was supposed to be a ‘shall’ became a ‘may’—and more often than not, it was a dead letter.

Some courts, of course, held their ground. They insisted on the presence of witnesses during searches and threw out cases where this procedural safeguard wasn’t followed. But those acquittals often came too late. In India, the process itself can be as damaging, if not worse, than the punishment. By the time the acquittal comes, a person’s reputation, career, and mental well-being have already suffered irreparable damage.

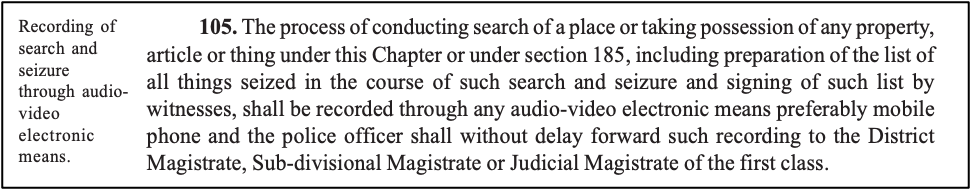

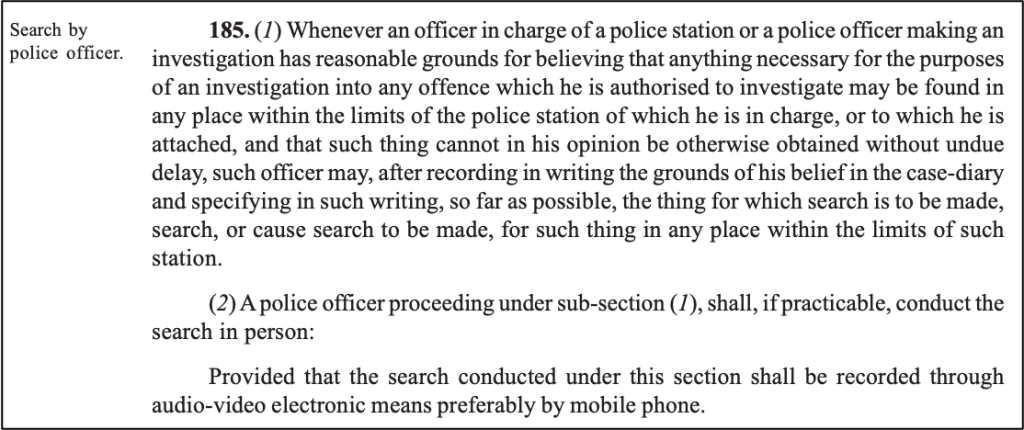

Enter BNSS. With its reforms, the landscape is shifting, offering a measure that may genuinely curb these abuses: mandatory videography of searches and seizures. Sections 105 (Search without Warrant) and 185 (Search with Warrant) of BNSS have transformed the earlier Sections 93 and 165 of the CrPC.

They read:

Here’s how it works:

- Every search of a place,

- Every instance of property, article, or thing being seized,

- The preparation of the list of seized items, signed by witnesses,

- All of this shall be recorded using audio-video means, preferably a cell phone,

- And this recording must be forwarded without delay to the District Magistrate, Sub-Divisional Magistrate, or a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class.

For searches conducted with a warrant (Section 185), this recording must be forwarded to the Magistrate within 48 hours.

This is, by all means, a welcome addition. And it is hoped that courts will ensure that this letter of the law is not only followed but also strengthened over time.

A Few Thoughts on the way forward:

- The Use of ‘Shall’:

The use of “shall” in these provisions suggests that videography is a mandatory requirement. But as experience tells us, Indian courts have sometimes allowed even mandatory provisions to become diluted. In this case, however, it is hoped that courts will treat this as a strict requirement. In situations where there is no justifiable reason for failing to record a search or seizure, courts should reject the evidence lock, stock and barrel. This may seem harsh, but it is a necessary stance. The law must set a high standard, and when it comes to criminal justice, the stakes are too high to allow procedural lapses. If courts overlook violations, law enforcement will have no incentive to improve. In some cases, excluding evidence might seem like an injustice (in that specific case), but this is a small sacrifice for the greater good—a stronger, fairer justice system. Cutting corners with procedural safeguards ought not to be taken lightly. - Lack of Infrastructure:

It’s easy to foresee law enforcement pleading a lack of equipment or infrastructure as an excuse for non-compliance. But such excuses must be scrutinized carefully and not accepted at face-value. A mobile phone is enough for recording, and in today’s digital age (with bandwidth being easy), it’s hard to imagine any officer without one. The argument of insufficient resources shouldn’t be entertained lightly. - Cell Phone Recordings:

The wording—“preferably through cell phone”—is practical but slightly problematic. While it acknowledges the ground reality that every officer has a phone, it also opens up new challenges. If the officer’s phone is used to record evidence, then that phone itself becomes critical primary evidence and should be preserved and examined to ensure the recording wasn’t tampered with. The forensic examination of the original device becomes even more crucial in cases where the authenticity of the evidence is in doubt. The phone should not just be a tool for recording but must be treated with the same care as any other piece of critical evidence. If the integrity of the device isn’t protected, it could jeopardize the entire case. But broadly speaking, videography through a dedicated device with a dedicated case specific memory card or similar medium is more desirable than a mobile phone and easier to admit in evidence. (I’ve been told that the Delhi Police proposes to use a portal to upload these videos. That’s good and may ensure timely and swift compliance. But the importance of preserving the device, or the original recording medium also needs to be considered). (Going forward – in fact- instead of separate devices, body-cams to be worn by the officers during search/seizures may even be better and less cumbersome). - Interplay with Section 63 BSA (Digital Evidence):

There’s also a need for clarity on how these provisions interact with Section 63 BSA, the updated version of Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act. For instance, who will issue the certificate of authenticity for digital evidence? This section of the law would benefit from further guidance. - Timing of Reportage:

There’s an odd distinction in the time-period (In which video has to be forwarded to Court) between searches with and without warrants. In the case of searches without a warrant, the video must be forwarded to the Magistrate without delay. For searches with a warrant, there’s a maximum time limit of 48 hours. The reasoning behind this difference is unclear. Swift forwarding in both cases should be the norm, ensuring early judicial scrutiny. - Inclusion of Section 27 IEA Statements & Personal Searches (upon arrest) within the ambit of these sections:

This requirement of a mandatory recording should also cover statements made under Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act and Personal Searches (upon arrest u/s 49 of BNSS) and Courts should interpret it as such. The Courts should not confine this protective provision only to Searches of places (with or without warrant) but also the above situations where the possibility of planting false articles is the maximum. The words ‘search’ and ‘seized’ in Section 49 BNSS (Search of Arrested Person) should derive their colour and meaning from the Section 105 and 185 of BNSS & those safeguards applied.. This would also comport with the intent of the legislature. It is well settled that a beneficial provision should be given its fullest play and its application should not be unduly narrowed or whittled lest Investigators find a way to plant objects upon the person of the accused instead of his – say – house or a place.

In conclusion, these provisions under BNSS are a significant step forward. However, the real test will be in their implementation. The courts must play a pivotal role in ensuring that these reforms don’t become yet another dead letter.

It’s crucial that the judiciary takes a hard line on non-compliance, setting a precedent that procedural fairness is absolutely non-negotiable.

Only then can this law serve its true purpose: to prevent false implications, protect individual rights, and restore faith in the criminal justice system.

Leave a reply to Pavni Gupta Cancel reply